Despite the loss of Edessa, the heartland of the crusader states was remarkably robust and resilient throughout this period.

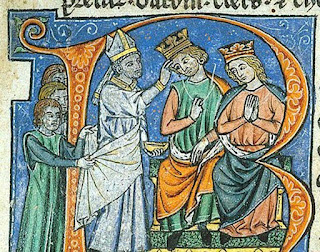

Baldwin II, who had no sons, was succeeded at his death in 1131 by his eldest daughter Melisende without controversy. She had married Fulk d’Anjou in 1129, and he was crowned co-regent with her in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The hereditary Count of Anjou, Fulk had taken the cross and served as an associate, temporary member of the Templars in the Holy Land in 1119-1121. After his heir Geoffrey married the daughter and heiress of King Henry I of England, the widowed Fulk abdicated Anjou in favor of his son and agreed to marry Melisende.

Jerusalem experienced and weathered its first serious constitutional crisis when Fulk tried to sideline his wife and co-regent Queen Melisende. The barons of Jerusalem suspected him of wanting to alienate the crown for a younger son from his first marriage and solidly backed Queen Melisende. Likewise, the ecclesiastical lords remained staunchly loyal to the queen. Insinuations of infidelity failed to undermine her position because the rumors were (rightly) dismissed as an attempt by her husband to discredit her. In the end, a man famed for his ability to bring rebellious vassals to heel was forced to respect his wife’s position of equal power. So much so, that William of Tyre writes: ‘But from that day forward, the king became so uxorious that, whereas he had formerly aroused [his wife’s] wrath, he now calmed it, and not even in unimportant cases did he take any measures without her knowledge and assistance.’ [i]

Furthermore, once a working relationship had been established between the co-monarchs, they worked together as an effective team. A natural division of labor evolved in which King Fulk focused on military and foreign affairs, while Queen Melisende managed the domestic administration of the kingdom. Due to Melisende’s status as ruling monarch (not merely queen-consort), there was no disruption in government when King Fulk died in a hunting accident 10 November 1143. Melisende continued to rule, now jointly-with her son Baldwin III, who was just 13 at the time of his father’s death. Although the kingdom was briefly roiled when in 1152 Baldwin resolved to push his mother aside and take sole control of government, the crisis was rapidly resolved without international or security repercussions. Baldwin III reigned until 1163, when he died childless, and was succeeded by his brother Amalric. Amalric was required to set aside his wife Agnes de Courtenay before the High Court would recognize him as king, but once he complied with this requirement, his succession was seamless and rapid. The kingdom remained stable.

Throughout this period, from 1131 when Melisende and Fulk were crowned until the death of Amalric in 1174, the Kingdom of Jerusalem enjoyed a period of peace and prosperity characterized by economic growth and development, the expansion of trading ties, the evolution of sophisticated judicial and financial systems, and decisive military superiority. It has been calculated that Muslims attacked twelve times less often during this period than in the first fifteen years of the kingdom’s existence. Furthermore, most major battles were ‘waged on Muslim ground in proximity to centres of Muslim population, and most ended in a decisive victory for the Franks.’[ii] Frankish superiority on the battlefield was so great that for most of this period the Saracens tried to avoid battle altogether. They preferred surprise raids on what we would call ‘soft’ targets. Furthermore, the Frankish army could muster and deploy so rapidly, that if Saracen raids ran into resistance, they broke off the attack before the kingdom’s military force could be brought to bear. Warfare of these period was, therefore, characterized by short raids of limited scope.

The exception to this was the Frankish capture of Ascalon in 1153 after an eight-month siege. This represented a major defeat for the Fatimids, who had invested heavily in holding on to the city. Ascalon was a base for the Egyptian fleet and as soon as it was lost to them, all the Frankish cities to the north became more secure as did merchant shipping in the Eastern Mediterranean. Furthermore, Ascalon had been a base for lightning raids into the interior of the kingdom, reaching as far as Hebron. To protect the surrounding region against these raids, in the early 1140s King Fulk ordered the construction of four major castles: Gaza, Blanchegarde, Bethgibelin, and Ibelin. At the same time (1142) the Baron of Transjordan built on Roman foundations the mighty castle of Kerak southeast of the Dead Sea. These castles, far from being indications of weakness and fear, represented the self-confidence of the Franks. They were bastions for projecting power, not places of refuge.

The growing importance and viability of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was also reflected in a shift in Byzantine foreign policy. Up to this time, Constantinoples’ relations with the crusader states were based on demands for submission to Byzantine suzerainty. While these claims were more formal or nominal in the case of Jerusalem itself, Byzantine efforts to regain control of Antioch were tenacious and largely successful, forcing the Princes of Antioch to recognize the Emperor as their overlord. Then, in 1155, the new Prince of Antioch, Reynald de Châtillon, provoked the just ire of Constantinople by raiding the Byzantine island of Cyprus and engaging in an orgy of savagery including the mutilation of prisoners, extortion, rape, pillage, and destruction. Although Châtillon was condemned by the Latin Church and Baldwin III of Jerusalem, his behavior reinforced existing Byzantine prejudices against the Latin Christians as ‘barbarians.’ Yet his savagery also surprisingly provoked change.

While Emperor Manuel I collected a large army to march against Châtillon, Baldwin III signaled agreement with the need to teach the violent Prince of Antioch a lesson. Châtillon rapidly recognized that he was trapped and friendless. In a dramatic gesture, he Manuel barefoot and bareheaded with a noose around his neck to symbolize his complete surrender to the Byzantine Emperor. After this incident, Manuel concluded that Baldwin III was worth cultivating. What followed were a series of strategic alliances symbolized by royal weddings. Two of Manuel’s nieces married successive Kings of Jerusalem (Theodora married Baldwin III in 1158 and Maria married Amalric I in 1167), and Manuel himself married Maria, the daughter of the Prince of Antioch in 1161.

One can see these marriages as a conscious attempt to civilize and subtly influence policy in Western courts, but Manuel was also willing to ransom prominent crusader lords languishing in Muslim captivity. Ransoming prominent prisoners created ties of gratitude, while also serving as public relations gestures that earned respect and admiration from the public at large. Thus, Manuel ransomed even his archenemy Reynald de Châtillon, as well as Bohemond III of Antioch and paid a king’s ransom (literally) for Baldwin d’Ibelin, the Baron of Ramla and Mirabel. Yet without doubt the most important feature of Manuel’s co-operative policies with the crusader states were a series of joint military operations. These included action against Nur ad-Din in 1158-59, an invasion of Egypt in 1167-68, and a joint siege of Damietta 1169.

The Frankish-Byzantine invasion of Egypt in 1167-68 was only one in a series of five military interventions in Egypt undertaken by King Amalric between 1163 and his death in 1174. The key characteristics of these operations were their opportunistic and the geopolitical character. Amalric’s interventions in Egypt had nothing whatever to do with ‘crusading.’ Nor were they in any way racist or religious much less genocidal. In all campaigns, Amalric was operating exactly like his Muslim (and Christian) neighbors in seeking geo-political and economic benefits. Ideology, not to mention idealism, was completely lacking.

Since the capture of Ascalon in 1153, the Fatimids had been paying ‘tribute’ to the Kings of Jerusalem, but the Fatimid state was rotting from the inside as two competing viziers, Dirgham and Shawar, intrigued against one another for power. Inevitably, the tribute disappeared into someone’s purse or was used for other purposes providing a pretext for a Frankish invasion in 1163. Amalric’s invasion force came within 35 miles of Cairo before the acting vizier Dirgham, panicked, agreed to an even larger ‘tribute,’ and Amalric withdrew. Unfortunately, the success of this campaign appears to have whet Amalric’s appetite for more. Egypt was fabulously wealthy, and the ruling Shia elite was not particularly popular with the majority Sunni population or the Coptic Christians, who still formed a significant minority. Amalric smelled blood.

Meanwhile, however, Dirgham’s rival Shawar had fled to Damascus and appealed to Nur al-Din for assistance. Nur al-Din sent one of his most reliable emirs, a Kurd by the name of Asad al-Din Shirkuh. Despite initial setbacks, Seljuk-backed Shawar was able to kill Frankish-backed Dirgham, only to discover that his ‘protector’ (Shirkuh) was intent on replacing him. Shawar immediately turned to the Franks for help. He offered Amalric payments greater than what Dirgham had paid to keep the Franks out, if the Franks would come in to fight his battles for him. In April 1164 Amalric obliged by returning to Egypt with an army. He rapidly put Shirkuh on the defensive, besieging him at Bilbies. But Nur al-Din countered by attacking Antioch. In the Battle of Artah on 10 August 1164, Nur al-Din decisively defeated a combined Frankish-Byzantine army, taking Bohemond III of Antioch, Raymond III of Tripoli, the Byzantine Dux Coloman, and Hugh VIII de Lusignan captive — effectively decapitating the entire Christian leadership in the northern crusader states. Once again, a catastrophe in the north undermined successes in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Amalric was forced to negotiate a truce in Egypt in order to address the situation in the north. Both the Franks and the Damascenes withdrew from Egypt, restoring the status quo ante.

Three years later, Nur al-Din made a renewed attempt to seize control of Egypt, and Shawar again turned to the Franks. Amalric initially enjoyed astonishing successes, aided by an Egyptian population that blamed the invading Turks/Kurds for their misery. He succeeded in capturing Alexandria, briefly taking Shirkuh’s nephew Salah al-Din — better known in the West as Saladin — captive, but he then accepted terms. The Turks withdrew and the Egyptians agreed to pay an even larger annual tribute (100,000 gold dinars) for Frankish ‘protection.’

Amalric, however, let his three-fold success delude him into thinking more was possible. He appears to have envisaged a powerful kingdom controlling the Nile as well as the Eastern Mediterranean. It was an alluring illusion. The capture of Egypt would have made the Kingdom of Jerusalem a major Mediterranean power — and a majority Muslim state. No King of Jerusalem and Egypt could have retained the mantle of ‘Protector of the Holy Sepulcher,’ and a Christian ruling elite in Egypt would sooner or later have become as unpopular as the Shia Fatimids.

However, Amalric, the Hospitallers, and the Italian city-states were mesmerized by the wealth of Egypt. While Manuel I of Constantinople was probably more realistic, he had little to lose and much to gain if Christian control could be extended. Egypt had, after all, once been a component part of the Eastern Roman Empire. Manuel therefore sent a substantial fleet including impressive horse transports.

In Jerusalem, however, significant opposition to yet another invasion of Egypt surfaced. An attack constituted a violation of the agreement with Shawar, and the Templars warned King Amalric not to make the mistake of the Second Crusade: attacking an ally and creating a new enemy. The Templars refused to take part in the invasion of 1168. William of Tyre likewise expressed the views of other clerics that warned a violation of the treaty with Shawar would displease God. The militants triumphed and the invasion went ahead.

Again, the Franks met with initial successes, taking Bilbais in three days and engaging in an orgy of plunder and murder without discriminating between Muslims or Coptic Christians; this atrocity turned the Copts against the Franks for years to come. Meanwhile, betrayed by his former friends the Franks, Shawar turned to his old enemy Nur al-Din. Meanwhile, the Franks advanced on Cairo. Shawar set fire to the old city to stop the Frankish advance, and then started bribing Amalric again. By then, however, Shirkuh had arrived with his Kurdish/Turkish Sunni army. This now threatened Amalric’s rear. The Franks chose to withdraw — all the way to Jerusalem. The Byzantine fleet likewise headed for home, only to run into storms which destroyed much of it. The campaign had become a fiasco.

Yet far more fateful, this blatant violation of international law triggered a regime change in Cairo. Shirkuh had rescued Shawar from the Franks, but Shawar had no credibility left. Within days of his arrival, the Kurdish emir had the Egyptian vizier murdered. The Sunni Shirkuh made himself vizier of Shia Egypt. Two months later, Shirkuh too was dead, apparently of over-eating. His successor was his nephew Saladin, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem would never be the same again.

[i] William of Tyre. A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, translated by Emily Atwater Babcock and A. C. Krey [New York: Octagon Books, 1976] Book XIV, Chapter 18, 76.

[ii] Ellenblum, 164.

This entry is an excerpt from Dr. Schrader's comprehensive study of the crusader states.

No comments:

Post a Comment