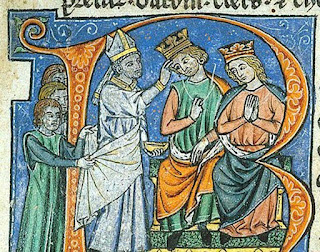

King Amalric of Jerusalem died unexpectedly only two months after Nur al-Din. He was only 38 years old and like Nur al-Din, Amalric left a minor heir, a youth who had just turned 13. Unlike Nur al-Din’s death, Amalric’s did not trigger a power struggle. None of Amalric’s vassals marched an army to his capital city; none of his barons staged a coup that sent his legitimate heir fleeing to the frontiers. On the contrary, although the constitution of Jerusalem gave the High Court the authority to elect kings — almost inviting rivalries and factionalism — consensus coalesced immediately around Amalric’s only son Baldwin. The youth was crowned Baldwin IV just four days after his father’s death.

Yet there was a problem. Roughly four years earlier, Baldwin had lost the feeling in his lower right arm. Although many doctors, including Arab doctors, had been consulted, no one found a cure. The possibility that Baldwin was suffering from leprosy was recognized, but not fully acknowledged at the time he ascended the throne. This may be because he was not severely disfigured or handicapped at the time of his father’s death. On the contrary, his face was not yet touched by the disease. Furthermore, he had not only been tutored by one of the leading scholars of the kingdom, he had received special riding instruction to enable him to control his horse with his legs alone. His outward appearance was still normal.

Even as his condition deteriorated and the name of his condition could no longer be denied, Baldwin IV was neither isolated nor forced to abdicate. The fact that the Christian barons, bishops and commons were prepared to submit to a leper astonished the Muslim world, while many today, familiar with horror stories about lepers being ostracized and reviled, are baffled by Baldwin IV’s ability to retain his crown. The explanation lies in the fact that the crusader kingdom with its dominant Orthodox population was heavily influenced by Byzantine traditions. These viewed leprosy not as a sign of sin and divine punishment but rather as a sign of grace. By the 4th century AD, the sufferings of Job were associated with leprosy, and leading theologians reminded the Christian community that lepers too had been made in God’s image and were likewise redeemed by Christ. Legends in which Christ appeared on earth as a leper were popular, and the disease was referred to as ‘the Holy Disease.’ This was the context in which Baldwin IV reigned.

Yet while these attitudes explain why Baldwin was never repudiated, Baldwin himself deserves credit for earning and retaining the loyalty of his subjects. Throughout his reign, even as his capabilities and appearance deteriorated, Baldwin never faced rebellion or insubordination. Nor was his reign characterized by exceptional factionalism, as popular literature is prone to suggest. Nevertheless, the combination of his deteriorating health and the need to find a suitable consort for his female heir, his sister Sibylla, eventually brought the kingdom to its knees.

During most of Baldwin’s minority, the regency was held by his closest male relative on his father’s side, Raymond Count of Tripoli. Tripoli was an able administrator, who sought consensus and enjoyed excellent relations with his fellow barons, the church and the military orders. He conscientiously negotiated a marriage for Sibylla with William ‘Longsword’ de Montferrat, an eminently suitable Western lord with close ties to the Holy Roman Emperor. In foreign and military affairs, Tripoli was cautious, rapidly concluding a truce with Saladin that lasted a year.

On July 15, 1176 Baldwin IV took the reins of government into his own hands. He was just fifteen and, perhaps due to his youth, proved far less circumspect than Tripoli. He immediately chose a course of confrontation with Saladin. Taking advantage of the fact that Saladin was attacking Aleppo, Baldwin personally led a raid into Damascene territory within two weeks of coming of age and defeated forces under Saladin’s brother Turanshah.

Baldwin also moved rapidly to renew ties with Constantinople, sending an ambassador there in the fall of 1176. Behind his keen interest in a Byzantine alliance lay Baldwin’s desire to pursue his father’s dream of conquering Egypt. To further these ambitions, Baldwin IV accepted Byzantine suzerainty on the same nominal terms as his father and furthermore accepted the appointment of an Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem. The impending arrival of a substantial crusading army under the Count of Flanders seemed the perfect opportunity for the Kingdom of Jerusalem to again take the offensive. With Saladin not yet firmly entrenched, prospects of success cannot be dismissed.

Before anything could be undertaken, however, both Baldwin and his brother-in-law became ill independently of one another. William de Montferrat died in June 1177, leaving behind a pregnant widow, and Baldwin had not yet recovered when Count Philip of Flanders arrived in Acre two months later. Indeed, Baldwin was so ill that he offered Flanders the regency of his kingdom. (Flanders, like Henry II of England, was Baldwin’s first cousin, through a daughter of Fulk d’Anjou by his first wife.)

Astonishingly, Flanders refused the regency of Jerusalem. Since Baldwin was still too ill to command his own army, focus turned to finding an interim commander-in-chief capable of leading the joint forces of Jerusalem, Flanders and Byzantium into Egypt. Baldwin chose the infamous Reynald de Châtillon, who had since married the heiress of Transjordan. However, Flanders again made problems because he expected to become king of whatever territory was conquered in Egypt; King Baldwin, however, had already agreed with the Byzantine Emperor that they would divide conquered territories between them. Mistrust of Flanders and his intentions led the Byzantines to angrily withdraw their fleet of seventy ships. Flanders, too, promptly abandoned the Egyptian campaign and took his troops to the Principality of Antioch in a huff. With him went the Master and knights of the Hospital, the knights of the County of Tripoli and roughly 100 knights from the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Saladin, who had been gathering troops on his northern border to face a combined Byzantine/Frankish/Flemish invasion found himself facing an infidel kingdom nearly denuded of troops and led by a bed-ridden, teenage king. No ruler in his right mind would have squandered such an opportunity. Saladin crossed into the Kingdom of Jerusalem with an army estimated at 26,000 Turkish light cavalry, including 1,000 Mamluks of Saladin’s bodyguard. Saladin’s intentions were unclear. Was this just a particularly strong raid to destroy, harass and terrify? Or did the Sultan hope to strike at Jerusalem itself and possibly put an end to the Christian kingdom?

The inhabitants of Jerusalem were thrown into a panic. Many sought refuge in the Tower of David because the walls of the city had been neglected in the decades of Frankish military superiority. Saladin’s first target, however, was Ascalon — the great bastion of Fatimid Egypt that had fallen into Frankish hands only a quarter century earlier.

King Baldwin, who weeks earlier had been willing to appoint a deputy (Reynald de Châtillon, Lord of Transjordan) to command his army for the invasion of Egypt, rose from his bed and assembled every knight he could. The Bishop of Bethlehem brought out the True Cross, a relic believed to be a fragment of the cross on which Christ was crucified. Riding at the head of this small force, Baldwin made a dash to Ascalon, arriving only hours before Saladin’s advance guard, on or about November 20.

Here, Baldwin apparently issued the arrière ban — the call to arms for every able-bodied man of the kingdom. With Saladin’s army enclosing Ascalon, however, it was unclear where the troops should muster. The forces Baldwin had already collected, 357 knights, did not impress Saladin. Concluding that he could keep the king and his paltry force bottled up in Ascalon with only a fraction of his own force, Saladin with the main body of his troops proceeded north to Ramla on November 22 or 23. His advance units had already spread out, looting, raping and burning, including the towns of Ramla, Lydda and Hebron. From Ramla, the main road lay wide open to the defenseless Jerusalem.

Behind Saladin, however, Baldwin sallied out of Ascalon. Rather than making a dash via Hebron to Jerusalem to defend his capital, the Frankish king chose to shadow Saladin’s army. With Saladin’s main force in Ramla, Baldwin mustered his army in Ibelin roughly 16 kilometers (13 miles) to the south. Either here or previously, he rendezvoused with the Templar Master at the head of eighty Templar Knights and, one presumes, roughly equal numbers of sergeants and turcopoles. The Templars had rushed south to defend their castle at Gaza only for Saladin to by-pass it. At Ibelin, too, the commoners responding to the arrière ban flooded in.

What Baldwin did next was not just courageous it was tactically sophisticated: he marched his army onto a secondary road leading to Jerusalem as if trying to slip past Saladin’s force at Ramla. Saladin took the bait and pursued. Michael Ehrlich in his detailed analysis of the battle based on both Frankish and Arab sources argues that by this feint Baldwin succeeded in maneuvering Saladin onto marshy ground beside a small river at the foot of a hill known as Montgisard. Here, as the Saracens crossed over the river, the Franks reversed their direction and fell upon their ‘pursuers.’ Ehrlich notes that: ‘In these conditions numerical superiority became a burden rather than an advantage. It demanded additional efforts to maneuver the trapped army, which fell into total chaos.’[i]

What followed was a complete victory for the Franks. The Sultan’s army was routed and fled in disorder. Many of Saladin’s troops were captured by pursuing Franks, others by local villagers set on revenge after the rape and pillage of Saladin’s marauding troops in the days before. Some of the fleeing Turks made it as far as the desert only to be captured and sold into slavery by the Bedouins, who also took advantage of Saladin’s defeat to plunder his baggage train left at his base camp of al-Arish. Saladin barely escaped with his life, fleeing on a pack camel and arriving in Cairo without either his army or his baggage. Not until his victory at Hattin did Saladin feel he had wiped out the shame of Montgisard. The cost to the Franks may have been as much as 1,100 dead and 750 wounded, but these numbers have been questioned and certainly were not corroborated by other sources. Certainly, no nobles were killed and very few if any knights.

Modern historians following Arab sources give Reynald de Châtillon credit for this astonishing victory. The Arabs, however, didn’t have a clue who was commanding at Montgisard, much less who had devised the strategy. Historians have also been mislead by the fact that Baldwin appointed Châtillon his ‘executive regent’ while he was so ill that he did not believe he could personally campaign. However, according to William of Tyre who was an intimate of Baldwin IV and his chancellor, the terms of Châtillon’s appointment were that he should command the royal army only in the absence of the king. Once Baldwin took the field — as he did most certainly did at Montgisard — that appointment was null and void.

The two contemporary Christian chronicles of the battle based on eye-witness accounts both identify King Baldwin as the commander of the overall army, while one adds the detail that the Baron of Ramla led the vanguard in accordance with the custom of the kingdom. The latter point is important as it makes it clear Ramla’s prominence was not invented by the chronicler after the fact. According to the custom of the kingdom, command of the vanguard always fell to the baron in whose territory a battle was fought; Montgisard was in the lordship of Ramla. Ehrlich also points out that the entire victory at Montgisard was predicated on superior knowledge of the terrain and the ability to maneuver Saladin into a disadvantageous geographic position. He summarizes: ‘Led by a local lord, who certainly knew the terrain better than anybody else on the battlefield, the Frankish army managed to defeat the Muslim army, in spite of its initial superiority.’[ii] Regardless of who masterminded the strategy that led to victory, the seventeen-year-old king, who had appeared on death’s door only weeks before, took sound advice, accepted risks, and rode with his troops although he could not wield a weapon. Is it any wonder that his subjects loved and trusted him thereafter?

Perhaps this astonishing and dramatic victory went to Baldwin’s head. One year later, in October 1178, he ordered the construction of a major castle at the ford across the Jordan known as ‘Jacob’s Ford.’ This was a vital strategic position, less than a day’s ride from Damascus at the gateway to Galilee, but it was also, at least from the Saracen point of view, on Saracen territory. Saladin first tried to bribe Baldwin into stopping work, offering a reported 100,000 dinars for him to dismantle the work already done. When Baldwin refused the bribe, Saladin attacked. Arab sources report that Saladin was so determined to destroy this castle that ‘he tore at the stones with his own hands.’[iii]

By the summer of 1179, the castle, although garrisoned by the Templars and functional, was not complete. The outer works, the second ring of what should have been a concentric fortress similar to Crak de Chevalliers, were still under construction. In early September 1179 Saladin attacked. The castle was undermined, parts of the walls collapsed, and the Templar commander threw himself into the flames as the Saracens broke in. The garrison and the construction workers were slaughtered and the wells poisoned — too soon it seems. Almost at once illness overwhelmed Saladin’s army, killing ten of his emirs and an unknown number of his troops.

Although the loss ‘Jacob’s Ford’ is often pointed to as the ‘beginning of the end’ of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, that judgement seems heavily colored by hindsight. The destruction of an incomplete castle built on Saracen territory did no more than re-establish the status quo ante. Saladin did not try to occupy and control the castle nor to build his own fortress at this location. Furthermore, he agreed to a two-year truce shortly afterwards. Yet there can be no question that for both the Sultan and the King the gauntlet had been thrown down and picked up; both were bent on hostilities.

Throughout the early 1180s, the Saracens made repeated raids on the borders of the kingdom and the audacity of these raids seemed to increase. In addition to this small-scale border raiding, Saladin undertook major campaigns against the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1182, 1183 and 1184. The campaign of 1182 was a full-scale invasion and the Franks, still commanded by Baldwin IV in person, defeated Saladin’s army at a day-long battle in intense heat at Le Forbelet. Although this was not the rout Montgisard had been, it was more than enough. Furthermore, Saladin’s better showing had more to do with Saladin having learned a lesson at Montgisard than with Frankish weakness.

The following year, Saladin again undertook a full-scale invasion, crossing the Jordan on September 29. The Franks mustered a huge army, allegedly numbering 1,300 knights and 15,000 foot. Saladin successfully raided round-about, and there were casualties on by sides in various skirmishes, but the decisive confrontation failed to materialize before Saladin was compelled by logistical factors to withdraw across the Jordan. The remaining two Saracen incursions prior to the campaign that led to the Battle of Hattin were both attempts to capture the border fortress of Kerak. In both cases Saladin broke off his siege as soon as a Frankish field army came to the relief of Kerak.

Yet it would be wrong to picture the Kingdom of Jerusalem as besieged and on the defensive throughout this period. King Baldwin personally led raids into Damascene territory in late 1182. In addition, Reynald de Châtillion twice initiated offensive operations, once striking at Tarbuk (1181-1182) and the next year launching ships in the Red Sea. Bernard Hamilton argues compellingly that both of these operations — far from being the actions of a ‘rogue baron’ intent on disrupting the (non-existent) peace for his own gain — had clear strategic aims. In the first case, the raid prevented Egyptian forces from reinforcing Saladin in his campaign against Aleppo and in the second case embarrassed him with his Muslim subjects during his campaign against Sunni Mosul. Baldwin IV had wisely concluded a ten-year alliance with Mosul that included substantial payments to the Franks.

Thus, when we look back on the reign of Baldwin IV (1174-1185) we see that Baldwin won all but one of the confrontations with Saladin in which he personally took part. (He was bested on the Litani in 1179, shortly before Saladin destroyed the castle at Jacob’s Ford). Furthermore, as late as the autumn of 1182, Baldwin was still leading raids into Damascene territory — on horseback. However, between phases of apparent vigor, Baldwin also had bouts of weakness when he was bedridden and seemed on the brink of death. These are recorded in the summer of 1177, in the summer of 1179, and again the summer of 1183. These bouts of illness were probably not, or only indirectly, related to his leprosy. Tyre refers to them as fevers, and the cyclical nature of the attacks suggests they may have been malaria. Yet, in addition to these periods of debilitating weakness, Baldwin IV was also disintegrating before the eyes of his subjects. He was dying a little more each day. Despite both these weaknesses, Baldwin’s reign would not appear one of increasing vulnerability were it not for a single fact: the succession had not been adequately resolved. It was the crisis over Baldwin’s successor that ultimately tore the kingdom apart — and then only after Baldwin himself had found eternal peace.

[i] Ehrlich, Michael. ‘Saint Catherine’s Day Miracle — the Battle of Montgisard,’ in Medieval Military History, Vol. XI [Woodbridge: Boydell, 2013] 105.

[ii] Ehrlich, 105.

[iii] Barber, Malcolm. ‘Frontier Warfare in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: The Campaign of Jacob’s Ford, 1178-179’ in The Crusades and their Sources, editors John France and Willaim G. Zajac. [Farnham: Ashgate, 1998] 14.

This entry is an excerpt from Dr. Schrader's comprehensive study of the crusader states.