The

The Kingdom of Heaven, a film directed by Ridley Scott and released by 20th

Century Fox in 2005, was based — very loosely — on the story of Balian d’Ibelin, a historical figure. Although Scott’s film was a brilliant piece of cinematography, the story of the real Balian d’Ibelin was not only different but arguably more fascinating than that of the Hollywood hero.

Below is a summary of the known facts about the historical figure.

Balian

was born in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1150. He was the third

son and fifth or sixth child of the first Baron of Ibelin and Helvis of

Ramla. In the year of his birh, his father died and his mother

remarried. He was almost certainly raised by the eldest of his brothers,

Hugh, who inherited the lordship of Ibelin at his father's death. In

1158, at the death of his mother, her title to the lordship of

Ramla/Mirabel passed to the second of the Ibelin brothers, Baldwin, who

was the oldest child of their father's second marriage to Helvis of

Ramla. In 1171, Hugh died childless, and the title of Ibelin also passed to Baldwin. Balian was a landless, younger son.

Balian

first enters history at the Battle of Montgisard in which he is consistently mentioned. The Frankish army spent the night before the battle at Ibelin, while Saladin's army occupied Ramla. The

battle itself took place within the lordship of Ramla, and, in

accordance with the customs of the kingdom (which gave leadership of the

vanguard to the baron in whose territory a battle was fought), Balian's older brother Baldwin of Ramla held the most prominent command position. Even more important, scholarship has shown that the Franks

effectively lured Saladin into a swampy area on a secondary road where his superior numbers were neutralized by the terrain. The victory was as much a function of intimate familiarity with the countryside as courage and audacity. The men with that intimate knowledge of the terrain

necessary to know where to trap Saladin were the two men who had grown

less than 20 miles away: Baldwin of Ramla and his younger brother

Balian.

"Montgisard" copyright Talento

Aside from his prominent mention among the leaders at

the battle (prominent because he was at this time not yet a baron)

evidence for Balian playing an important -- if unclear -- role in the

battle is provided by the fact that at this time King Baldwin IV

approved his marriage to the Dowager Queen and Byzantine princess Maria

Comnena. This match can best be described as "scandalously"

advantageous. Notably, however, there is no hint of scandal or disapproval either. Whatever Balian had done

to win this unique honor, it met with the approval of the kingdom's

chancellor, the Archbishop of Tyre.

|

| Above: Maria Comnena and her 1st Husband King Amalric |

Maria

Comnena brought with her into the marriage her dower portion: the barony of Nablus. This large and prosperous barony owed fully 85 knights to the feudal muster, but it was not a hereditary title. It would revert back to the crown at Maria's death. Nevertheless, Balian is henceforth often referred to as Baron of Nablus. To secure an inheritance for children of his marriage with Maria, it appears his brother Baldwin transferred to him the barony of Ibelin at roughly the same time. With this

marriage, Balian also became step-father to King Baldwin's half-sister,

Isabella, his wife's child from her first marriage with King Amalric.

From this point onwards, Balain took part in all of the major military campaigns of the next decade and was also a member of the High Court of Jerusalem. Significantly, in 1183 when Baldwin IV decided to crown his nephew during his own lifetime to reduce the risk of a succession crisis, Balian was selected -- ahead of all the more senior and important barons in the kingdom -- to carry the child on his shoulders to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

From this point onwards, Balain took part in all of the major military campaigns of the next decade and was also a member of the High Court of Jerusalem. Significantly, in 1183 when Baldwin IV decided to crown his nephew during his own lifetime to reduce the risk of a succession crisis, Balian was selected -- ahead of all the more senior and important barons in the kingdom -- to carry the child on his shoulders to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

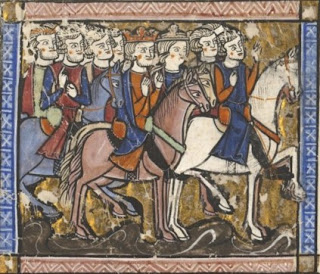

|

| A medieval depiction of this event: Balian holding Baldwin V |

At the death of Baldwin V in the summer of 1186, Balian took a leading role in opposing the usurpation of the throne by Sibylla of Jerusalem and most especially her devious tactics to get her unpopular second husband, Guy de Lusignan, crowned as her consort. At his wife's dower property of Nablus, just north of Jerusalem, Balian hosted a meeting of the majority of the High Court -- all those opposed to Sibylla and Guy. At this rump-High Court, the bishops and barons proposed crowning Sibylla's half-sister (Balian's step-daughter) Isabella Queen of Jerusalem as the legitimate rival to Sibylla and Guy. These plans were thwarted by Isabella's young husband, Humphrey of Toron, who secretly did homage to Guy, robbing Isabella's supporters of a viable alternative to Sibylla/Guy.

In consequence, the majority of the barons became reconciled with Sibylla and Guy's usurpation and did homage to them, but Balian's older brother, Baldwin of Ramla/Mirabel, refused. Instead, in a dramatic gesture, he abdicated his titles in favor of his small son and gave both the boy and his baronies into the keeping of his brother Balian. He then quit the Kingdom to seek his fortune in the Principality of Antioch and disappears from the historical record.

With the departure of his brother, Balian was suddenly elevated to one of the most powerful barons in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, controlling (in the name of his nephew and wife) the second-largest contingent of feudal levies owed to the crown. He used this power to try to reconcile the usurper, Guy de Lusignan, with the only baron more powerful than himself: Raymond Count of Tripoli. The latter, like his brother, was refusing to do homage to Guy, despite the clear and present danger posed by Saladin.

Balian was ultimately successful in his reconciliation efforts, and shortly afterward, Balian and Raymond demonstrated their loyalty to the crown by answering the royal summons to muster under the leadership of Guy de Lusignan when he faced Saladin’s invasion of July 1187. Against the the advice of the majority of the barons, Guy chose to abandon the Springs of Sephorie and march the army across an arid plateau to the relief of the beleaguered city of Tiberius. The siege of Tiberius was bait, and Guy led the army into a trap set by Saladin that ended in the disastrous defeat of the Christian army on the Horns of Hattin.

Balian was

one of only three Christian barons to escape the debacle. Exactly, how,

he escaped capture is not recorded, however, contemporary sources say he was in command of the rear-guard, so it is possible that he managed to fight his way out the way he'd come. (Note, however, that the rear-guard had been savagely attacked throughout the previous day.) Arab sources also note that toward the end of

the battle, the Franks Ied a more than one charge, one of which

endangered Saladin himself. Possibly, one of these broke through the

surrounding Saracen army enough to let Balian and some of his knights

escape. However, he escaped, he is believed to have ridden to Tyre or

Tripoli with the men he led out of the encirclement.

The destruction or capture of the bulk of the Christian army, however, left the Kingdom of Jerusalem undefended. Saladin followed up his victory at Hattin by capturing one city and castle after another until, by the start of September 1187, Saladin controlled the entire Kingdom of Jerusalem except for some isolated castles, the city of Tyre, and the greatest prize of all: Jerusalem.

In Jerusalem were concentrated somewhere between 60,000 and 100,000 Christians; twenty thousand inhabitants and between forty and eighty thousand refugees from the territories Saladin had already conquered. But there were no knights in Jerusalem and no commander. Saladin called a delegation from Jerusalem to him at Ascalon and offered to let those trapped in the city go free in exchange for the surrender of the city. The representatives from Jerusalem refused. According to Arab sources, they said that Jerusalem was sacred to their faith and that they could not surrender it; they preferred martyrdom. Saladin vowed to slaughter everyone in the city since it had defied him.

Among the refugees in the city of Jerusalem were Balian’s wife, the Dowager Queen of Jerusalem, and his four young children. Balian had no intention of letting his wife and children be slaughtered and so he approached Saladin and requested a safe-conduct to ride to Jerusalem and remove his wife and children. Saladin agreed -- on the condition that he ride to Jerusalem unarmed and stay only one night.

Balian had not reckoned with the reaction of the residents and refugees in Jerusalem. The arrival of a battle-tested baron -- one of only two who had escaped Hattin with his honor still intact -- was seen as divine intervention and the citizens along with the Patriarch of Jerusalem begged Balian to take command of the defense. The Patriarch demonstratively absolved him of his oath to Saladin. Balian felt he had no choice. He sent word to Saladin of his predicament and Saladin graciously sent 50 of his own men to escort Balian’s family to the Tripoli (still in Christian hands), while Balian remained to defend Jerusalem against overwhelming odds.

And defend Jerusalem he did -- despite there being fifty women and children in the city for every man, and despite having only one other knight to fight with him. He hastily knighted sixty to eighty youth "of good birth" and organized the civilian population. Probably with native troops (turcopoles) he conducted foraging sorties to collect supplies for the population from the surrounding Saracen-held territory in the days prior to the siege. Once the city was enclosed, he successfully held off assaults from Saladin’s army from September 21 – 25, and led sorties that in at least one case drove the Saracens all the way back to their camp. Saladin was forced to re-deploy his army against a different sector of the wall. On September 29, Saladin’s sappers successfully undermined a portion of the wall and brought down a segment roughly 30 meters long. Jerusalem was no longer defensible.

It

was now that Balian proved his talent as a diplomat. With Saracen forces pouring over the breach and into the city, their banners flying from one of the nearest towers, Balian went to Saladin to negotiate.

According to Arab sources, Saladin scoffed: one doesn’t negotiate the

surrender of a city that has already fallen.

But as he dismissively pointed to his banners on the walls of the city, those banners were thrown down and replaced again by the banners of Jerusalem. Balian played his trump. If the Sultan would not give him terms, he and his men would not only kill the Muslim prisoners they held along with all the inhabitants: they would desecrate and destroy the temples of all religions in the city, including the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque before sallying out to die a martyrs death taking as many as the enemy with them as possible. Saladin gave in.

The Christians were given 40 days to raise ransoms of 10 dinars per man, 5 per woman and 2 per child. Realizing that many refugees who had already lost everything would be unable to raise these sums, Balian talked Saladin into accepting 30,000 dinars for 18,000 paupers. His negotiations saved somewhere between forty and sixty thousand men, women and children from slaughter or slavery. Yet he could not find the resources inside Jerusalem to save everyone. When the forty days were up, an estimated fifteen thousand Christians were still marched off into slavery despite Balian's offer to stand surety for the ransoms, while efforts were made to raise their ransoms in the west. Saladin rejected the offer, but "gave" Balian 500 slaves as a personal gift. (I.e. he freed 500 Christians that would otherwise have gone into slavery.) He gave the same number to the Patriarch, who had also offered to stand surety according to some accounts.

Balian escorted a column consisting of roughly one-third of refugees from Jerusalem to Tyre, the closest city still in Christian hands. The man commanding Tyre at the time, Conrad de Montferrat, however, could not admit fifteen thousand more people to a city already under siege and at risk of starvation if relief did not come from the West. So while the bulk of the non-combatants continued to Tripoli, Balian and other fighting men remained in Tyre to continue the fight against Saladin.

In 1188, Saladin released Guy de Lusignan, taken captive at Hattin, but Montferrat refused to either admit him to the city of Tyre or recognize him as king. On the advice of his brother Geoffrey, recently arrived from France, Guy de Lusignan laid siege to the city of Acre, formerly the most important port of the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem and now in Saracen hands. Balian, despite his profound disagreements with Guy, joined him there; his determination to recapture some of the former kingdom was more important to him than his disagreements with Guy de Lusignan.

|

| Above: the surrender of Acre to Philip II of France during the Third Crusade |

When

Queen Sibylla of Jerusalem and both her daughters by Guy de Lusignan died in 1190, however, the situation changed for Balian. Guy's claim to the throne was through his wife. With her death, the legitimate queen of

Jerusalem was Balian's step-daughter, Isabella. Isabella had been

married since the age of 11 to an ineffectual young nobleman, Humphrey

de Toron. Realizing that the Kingdom at this time needed a fighting man as its king, Balian and his wife convinced Isabella to set Humphrey aside on the grounds that she had been forced into the marriage against her will before reaching the legal age of consent. (She had been

forcibly separated from her mother and step-father at age eight and

married at age eleven.) Having divorced Toron, she at once married

Conrad de Montferrat.

Thereafter, Balian staunchly supported Conrad de Montferrat as King of Jerusalem. This initially put him in direct conflict with Richard I of England, who backed Guy de Lusignan, the latter being the brother of one of his vassals. As a result, during the first year of Richard’s presence in the Holy Land, Balian remained persona non grata in Richard’s court. In fact, he served as an envoy for Conrad de Montferrat to the Sultan’s court — something Richard’s entourage and chroniclers viewed as nothing short of outright treason to the Christian cause.

Richard

the Lionheart, however, was neither a fool nor a bigot. He recognized

that after he went home (as he must) only the barons and knights of

Outremer could defend the territories he had conquered in the course of

the Third Crusade. He also reluctantly recognized that Guy de Lusignan

would never be accepted as King by the barons and knights of the Kingdom

he had led to a disastrous defeat at Hattin. So in April 1192, Richard

withdrew his support for Lusignan and recognized Isabella and her

husband as the rightful rulers of Jerusalem.

By In doing so, he opened the doors to cooperation with Balian d’Ibelin. Soon thereafter, Richard employed Ibelin as a negotiator with Saladin and in August Balian cut a deal with Saladin that provided for a three-year truce (neither side wanted peace for both were unsatisfied with the status quo). This truce did, however, allow unarmed Christian pilgrims to visit Jerusalem. Like the surrender of Jerusalem five years earlier, this was not a triumph -- but it was far better than what might have otherwise been expected under the circumstances. Notably, Balian's truce left Ibelin and Ramla in Muslim hands, something that he must have negotiated with a heavy heart. He was compensated, allegedly at Saladin's initiative, with the barony of Caymont near Acre.

Richard the Lionhearted returned to Europe and Isabella was crowned Queen of the much reduced but nevertheless viable Kingdom of Jerusalem. The man crowned as her consort was not, however, Conrad de Montferrat, who had fallen victim to an assassin only shortly before her coronation. Instead, her consort was her third husband, Henry of Champagne, a French nobleman, who had come out to the Holy Land for the Third Crusade. (Henry of Champagne was a grandson of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Louis VII of France, which made him a nephew of both Philip II of France and Richard of England.)

Balian was the leading nobleman in his stepdaughter's kingdom, but he disappears from the historical record in 1194. It is usually presumed that he died about this time, but it is equally possible that instead he was simply out of the kingdom, possibly on a diplomatic mission -- or helping his niece and her husband establish Latin rule on Cyprus. See: The Ibelins on Cyprus and the Role of a Byzantine Princess.

Whenever he died, Balian left behind two sons, John and Philip. John became Constable of Jerusalem in 1198, Lord of Beirut, and Regent of Jerusalem from 1205 - 1210. He also led the baronial revolt against Emperor Frederick II. Philip was to be Regent of the Kingdom of Cyprus 1218-1227. From these sons the Ibelin dynasty descended, a family often described as the most powerful of all baronial families in the Latin states of the Eastern Mediterranean for the next three hundred years.

Continued, in-depth research in preparation for the release of my non-fiction study of the crusader states with Pen & Sword had resulted in new insights and understanding of Balian and his environment, inducing me to undertake a major revision of Knight of Jerusalem. The new edition will be released later this year. Meanwhile, the current edition remains on the market as part of the Jerusalem Trilogy:

No comments:

Post a Comment