Today Dr Schrader continues her mini-series on opportunities for women in the Middle Ages with a look at women's access to economic power.

Nothing

gives women more power and status than wealth. In societies where women

cannot own property (e.g. ancient Athens) they are not only powerless

to take their fate into their own hands in an emergency, they are also

generally viewed by men as worthless. Where women can possess, pass-on,

and control wealth, they enjoy independence, respect and are viewed

(and coveted) not only as sexual objects but as contributors to a man’s

status and fortune (e.g. ancient Sparta).

Medieval

women across Europe could inherit, own and dispose of property. The

laws obviously varied from realm to realm and over time, but the

fundamental right of women to inherit was widespread and reached from

the top of society (women could in many but not all realms bequeath

kingdoms) to the bottom, where peasant women could also inherit and

transmit the hereditary rights to their father’s lands, mill or shop.

Significantly, it was not only heiresses

that enjoyed property and the benefits thereof. On the contrary, every

noblewoman received land from her husband’s estate at marriage called a

“dower.”

A

dower is not to be confused with the dowry. A dowry was not an

inheritance. It was property that a maiden took with her into her

marriage. Negotiated between families before a marriage, dowries were

usually land. Royal brides brought entire lordships into their marriage

(e.g. the Vexin), but the lesser lords might bestow a manor or two and

the daughters of gentry might bring a mill or the like to their

husbands. Even peasant girls might call a pasture or orchard their

dowry. The key thing to remember about dowries, however, is that they

were not the property of the bride. They passed from her guardian to her husband.

Dowers, on the other hand, were women’s property. In the early Middle Ages, dowers were inalienable

land bestowed on a wife at the time of her marriage. A woman owned and

controlled her dower property, and she retained complete control of this

property not only after her husband’s death, but even if her husband

were to fall foul of the king, be attained for treason, and forfeit his

own land and titles.

Whatever the source of a woman's wealth, in Medieval France, England and Outremer, women did not

need their husband’s permission or consent to dispose over their own

property. There are thousands of medieval deeds that make this point.

While it was common to include spouses and children on deeds, this was a

courtesy that increased the value of the deed rather than a necessity ―

and that principle applied to men as well as women. Thus many deeds

issued by kings and lords included wives and children as witnesses as a

means of demonstrating that the grant or sale was known to their

co-owners/heirs.

Middle-class

women could inherit whole businesses, and as widows they ran these

businesses, representing them in the respective guilds. Indeed, most

wives were active in their husband's business while he was still alive.

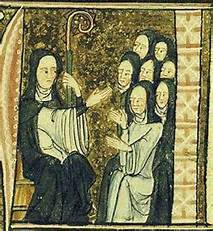

Manuscript illustrations show, for example, a women bankers (collecting

loans, while the husband gives them out), and "alewives" -- including

women in helmets bringing refreshment to archers engaged in a battle! (I

could not find that picture on the internet, but here's another

allegorical picture of women fighting.)

More important, however, women could learn and engage in trades and business on their own. They could do this as widows, as single, unmarried women (femme sole)

or as married women, running a separate business from that of their

husbands. The skills acquired, even more than property, fostered

economic independence and empowerment because property can be lost — in a

fire, an invasion, from imprudence and debt — but skills are mobile and

enduring, as long as one remains healthy enough to pursue one’s

profession. Furthermore, once qualified in a trade, women took part in

the administration of their respective profession, both as guild-members

and on industrial tribunals that investigated allegations of fraud,

malpractice and the like. In short, there was no discrimination against qualified women engaged in a specific trade.

Furthermore,

women in the Middle Ages could learn a variety of trades. Some trades

were dominated by women, for example, in England brewing, in France

baking, and almost everywhere silk-making. However,

women were also very frequently shopkeepers, selling everything from

fruit and vegetables (not very lucrative) to spices and books. In

addition, women could be, among other things, confectioners,

candle-makers, cobblers, and buckle-makers. Women could also be

musicians, copiers, illuminators, and painters, though I have not come

across references to women sculptors. More surprising to modern readers,

medieval records (usually tax rolls) also list women coppersmiths,

goldsmiths, locksmiths, and armorers. A survey of registered trades in

Frankfurt for the period from 1320 to 1500 shows that of a total 154

trades, 35 were reserved for women, but the remainder were practiced by both men and women, although men dominated in 81 of these.

Notably,

in the early Middle Ages women could be medical practitioners. All

midwives were women, of course, and sisters of the Hospital provided

most of the care for women patients, but women could also be barbers

(who performed many medical procedures such as blood-letting),

apothecaries, surgeons, and physicians. A female doctor, for example,

accompanied King Louis IX on crusade in the mid-13th century. Women

learned these trades in the traditional way, by apprenticing with

someone already practicing the profession, who was willing to take them

on. It wasn't until the 14th century that universities imposed the

exclusive right to certify physicians -- while excluding women from

universities.

All

Dr Schrader's novels set in the Middle Ages strive to show women as active

participants in society and the economy.

For

readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P.

Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures

based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her

complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to

better understand ourselves.

Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/crusades.html