The development of "fighting boxes" composed of infantry and cavalry fighting -- and moving -- as a tightly disciplined unit was a radical innovation in the fighting tactics of the medieval armies of the 12th and 13th centuries. The Frankish armies of Outremer developed and employed this tactic to great effect in countless battles, but it was not the only tactical innovation that enabled the crusader states to survive despite being surrounded by numerically superior enemies intent on pushing them into the sea. The other -- far too often overlooked -- innovation was the introduction of mounted archers. Yuval Harari has provided documentation to show that this arm made up on average 50% of the mounted strength of the armies of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Today Dr. Schrader looks at the forgotten mounted archers of the crusader states.

There was no tradition of mounted archers in Western Europe due to: 1) the cost of raising and maintaining horses of sufficient strength, agility, and intelligence to be suitable for mounted combat and 2) to the broken and wooded terrain that did not favor this kind of troops. The limited numbers of horses suitable for combat were bred to carry knights in full armor, i.e. for strength more than speed. The weapons of the knights, furthermore, were the lance and the sword, and the ethos of chivalry was one of individual "prowess" in close combat, man-to-man. Archery, by nature a long-distance weapon, was the province of mercenaries (who were proficient with cross-bows) and, later, the "yeoman" class that became the backbone of later English armies with their unique longbows. But that was still in the future. In the age of the crusades, "archery" in Europe was viewed primarily as a defensive weapon, useful first and foremost in siege warfare.

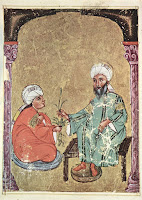

In the Middle East, in contrast, the open steppe was ideal both for the breeding, rearing and the deployment of light cavalry. The Crusaders came in contact with the superb horse-archers of the Turks almost as soon as they crossed into Asia. Turkish mounted archers had by the First Crusade already conquered most of central Asia. They were a formidable enemy and the Franks who settled in Outremer and faced the Turkish archers in every engagement learned to respect them. They also rapidly recognized the advantages that this kind of warrior offered in the environment that they now inhabited.

The fighting box (described last week) was a tactical formation that protected the heavy cavalry and enabled it to save its strength for a massed charged. It was invaluable during a fighting retreat. It was highly effective in a set-piece battle. But it was worthless for other kinds of military operations.

The Franks recognized that they needed light cavalry capable of conducting reconnaissance, conducting hit-and-run raids, and providing a protective screen for their “fighting box.” While the first two of these functions were handled by knights in the West, this option was not available in the crusader states because of the nature of the terrain and the enemy. The heavy horses of the Franks, bred to carry fully armored knights, could not — one on one — escape the faster lighter horses of the Turks. Heavy cavalry deployed on reconnaissance, therefore, was more likely to be ambushed and eliminated than get back with the intelligence needed by the main army.

Light cavalry could also be used for hit-and-run raids against enemy camps or territory. Again, only the faster, native horses carrying lightly armored riders armed with bows were suitable for this kind of task. Light cavalry was also essential for communication as fleet messengers who at least had a chance of out-running any enemy were necessary to bring messages from one army unit to another or between a castle and a field army.

The Franks not only recognized the need for light cavalry, they were remarkably rapid in developing it. Already by 1109, there are references in the primary sources to these troops. From that point forward, they played an increasingly important role in the fighting tactics and military successes of the Frankish armies of Outremer, in some cases operating independently, and in other cases in support of the infantry and heavy cavalry. Like the “fighting box,” they contributed substantially to the ability of the Frankish kingdoms to survive for two hundred years despite being dramatically outnumbered by their opponents.

That is a remarkable achievement. Mastering horsemanship to the point where a man could survive in mounted combat took years -- literally. The 13th-century scholar Philip de Novare noted: "he will never ride well who did not learn it when young."[1] Mastering archery even from solid ground took equally as long. Becoming an effectively mounted archer took years and years of very hard, concentrated training. It did not happen overnight. It required having the time (i.e. leisure) to train and the money for horses -- one of the most expensive commodities in the Middle Ages. In short, poor people did not become mounted archers -- unless they were the slaves of rich people such as the Mamluks of the Saracens. This was not the tradition in the Crusader kingdoms that never employed slave soldiers in any capacity.

So who were the mounted archers of the Crusader kingdoms and where did they come from?

Frankish mounted archers are misleadingly but consistently referred to as “Turcopoles” in the primary sources of the period. Despite the name, which was borrowed from the Byzantines, the term “Turcopole” in the context of the crusader states refers not to an ethnic group but simply to “mounted archers” — of diverse ethnic character.

Frankish mounted archers are misleadingly but consistently referred to as “Turcopoles” in the primary sources of the period. Despite the name, which was borrowed from the Byzantines, the term “Turcopole” in the context of the crusader states refers not to an ethnic group but simply to “mounted archers” — of diverse ethnic character.

The “Turcopoles” were not Muslim converts much less Muslim troops, as Yuval Harari demonstrates in his lengthy essay on the topic. [2] Harari notes:

"Though the scale of Muslim conversion and desertion was relatively extensive...it is doubtful whether the Franks in general, and the military orders in particular, would have agreed to rely on troops of Muslim origin." [3]

Furthermore, had they been apostate Muslims they would have been the object of outrage and horror in the entire Islamic world, something that would have been reflected in Muslim sources -- and is not. On the contrary, not only are they referred to neutrally there are numerous instances of prisoner exchanges involving Turcopoles. Had the Turcopoles been apostate Muslims that would have been impossible, since Sharia law prescribes execution for anyone who abjures Islam. There is not one instance where Turcopoles are singled out for verbal or physical abuse in the Muslim sources -- most of which were written by religious scholars with an acute sense of religious duty and understanding of Sharia law.

Nor were the Turcopoles the children of mixed marriages. Harari notes that in all his research he failed to find a single documented case of a "half-caste Turcople."[4] The numbers also speak against this thesis. The number of Turcopoles at the Battle of Hattin alone, for example, was 4,000 according to the Brevis Historia. Based on numbers at 16 different engagements and other references, Harari concludes that the Turcopoles made up on average 50% of the mounted force fielded by the Franks.[5] Furthermore, both the Templars and Hospitallers had Turcopoles integrated into their organizations and their Rule carefully accounts for them.

The most reasonable explanation of who the Turcopoles were is that they were primarily native (Orthodox) Christians. The principal objection to this conclusion is that four hundred years of Muslim oppression during which the Christian population had been prohibited from riding horses and carrying arms eliminated any military traditions and capacity. Certainly -- in the first generation. Which, incidentally, explains why the Turcopoles referred to in the early battles did not do particularly well. Two to three generations later, however, the situation was obviously different. Furthermore, the argument of "no military tradition" does not apply to the Armenians, who were a significant minority in the crusader kingdoms. There are also documented cases of native Christians becoming knights.[6] Indeed, there are instances of native Christians commanded Franks. [7] If they could become knights (i.e. heavy cavalrymen), there is no reason why they could not have become light cavalrymen.

Last but not least, the value of light cavalry in the context of Outremer increased if the Frankish light cavalry would pass for Turkish cavalry if necessary and blend in with a native population that consisted primarily of Orthodox Christians with a large Muslim minority. These characteristics and a fluent/native command of Arabic was essential for Turcopoles to conduct intelligence and reconnaissance effectively -- as they demonstrably did on numerous occasions. As I have pointed out elsewhere, the excellence intelligence enjoyed by the Kingdom Jerusalem enabled the Franks to muster their armies in time to confront invading Muslim forces again and again. Indeed, Michael Ehrlich in his reassessment of the Battle of Montgisard in 1177, underlines how superior Frankish reconnaissance and intelligence was in this battle so often treated as "a miracle" or simply "good luck" and daring. [8]

[1] Novare quoted in Joshua Prawer, "Social Classes in the Latin KIngdom," A History of the Crusades Volume Five: The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East," editors Norman Zacour and Harry Hazard (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1985) 125.

[2] Yuval Harari, “The Military role of the Frankish Turcopoles: A Reassessment,” Mediterranean Historical Review, 12:1, 75-116.

[3] Harari, 105.

[4] Harari, 102.

[5] Harari, 75-86.

[6] Christopher MacEvitt, The Crusades and the Christian World of the East: Rought Tolerance (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Univ. Press, 2008), 153-156.

[7] Harari, 104.

[8] Michael Ehrlich, "Saint Cather's Day Miracle - the Battle of Montgisard," Journal of Medieval Military History, Vol. XI, 95-106.

Turcopoles feature in nearly all Dr. Schrader's novels set in the crusader states, particularly Knight of Jerusalem and Rebels against Tyranny.

Dr. Helena P. Schrader holds a PhD in History.

She is the Chief Editor of the Real Crusades History Blog.

She is an award-winning novelist and author of numerous books both fiction and non-fiction. Her three-part biography of Balian d'Ibelin won a total of 14 literary accolades. Her current series describes the civil war in Outremer between Emperor Frederick andthe barons led by John d'Ibelin the Lord of Beirut. Dr. Schrader is also working on a non-fiction book describing the crusader kingdoms. You can find out more at: http://crusaderkingdoms.com